Barrett's

What is Barrett's?

The oesophagus (gullet) is a muscular tube that helps channel food from the mouth to the stomach. The stomach makes acid and enzymes to help digest food. Between the oesophagus and stomach a valve prevents acid, bile and other stomach contents from refluxing back into the oesophagus. About 20% of individuals have gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) where this valve is weak and fluid including acid and bile refluxes back onto the oesophagus causing regular disruptive heartburn, an acidic taste or disruption to the oesophagus lining and scarring.

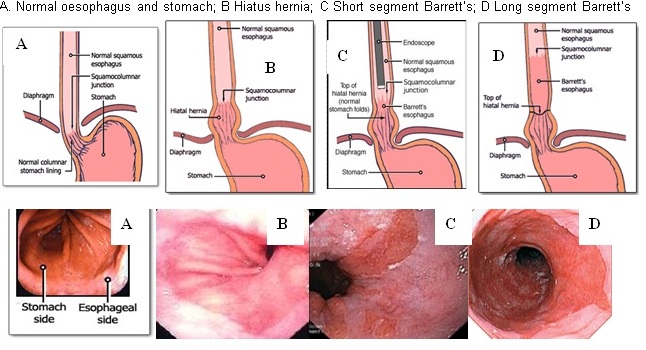

About 1 in 50 of the general population or 1 in 8 “refluxers”, get a gradual change in the lining cells of the lower oesophagus called Barrett’s oesophagus. The usual microscopic “white tiles,” change to microscopic specialised “red bricks.” These specialised “bricks” produce mucus which may be a clever way of the oesophagus protecting itself against the daily damage from acid and bile refluxing back up from the stomach. Most of people can’t feel this reflux, so 95% of people with Barrett’s may be blissfully unaware.

Barrett’s in some is a pre-cancerous lesion and it accounts for more than 95% of cases of oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OAC). However, the cancer risk is lower than previously believed. The incidence in patients with non-dysplastic Barrett’s is low at between 0.1% to 0.3% per year. So, the majority of Barrett’s patients will never develop OAC. Much effort has been made to try to define these high-risk patients likely to progress to OAC and effective preventive measures. Many questions are unanswerable to date and scientific debates continue.

Why does Barrett's matter?

Barrett’s is linked to a slight increased risk of oesophagus cancer. This is much like the way an abnormal pap smear is linked to cervix cancer or smoking to lung cancer. Also, just as most women with an abnormal pap smear will have an anxious wait for further testing to get an all clear, Barrett’s patients have a similar experience as over 95% have a normal life expendancy and DO NOT get oesophagus cancer. Also, oesophagus cancer is far less common than lung, breast or bowel cancer. So when diagnosed with Barrett’s, it is important to be clear about the low risk of problems. Once diagnosed, regular gastroscopies are often recommended every few years to decrease this risk even further.

Are there high and low risk Barrett’s groups?

The highest risk is in patients found to have high risk oesophagus cells (called “dysplasia”) when biopsied tissue is examined under the microscope. Dysplasia is pre-cancerous, so we currently believe if you have no dysplasia, you don’t get cancer. There are groups which may be at higher risk of dysplasia. It is more common in obese Caucasian males with heartburn and less common in females. It is found more often in a long-segment Barrett’s >3cm (0.5% of GORD) and less in short-segment <3cm (15% of GORD). For example, a 60 year old, obese, Caucasian male with 20 years of reflux symptoms and 8 cm “long segment” Barrett’s with erosions and dysplasia is in a high risk group for cancer and needs close endoscopic surveillance. A 60 year old, non-Caucasian female with minimal heartburn symptoms and 1cm Barrett’s segment without dysplasia is in a low risk group (<0.5% per year) and may choose no surveillance.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis of Barrett’s is important but it is not easy even for an expert. Several conditions look extremely similar but don’t have the same cancer risk. The definition has changed several times since it was first described by an Australian born surgeon, Norman Barrett in 1950. At the time of gastroscopy, the specialist will pinch off a small piece of tissue (a biopsy) and send it for expert microscopic analysis. The doctor doing your gastroscopy will only take biopsies that are absolutely necessary and ensure they have an expert review. If dysplasia – a precancerous change – is suspected, a second expert pathologist will be asked to review the specimens. Only if two expert pathologists agree is the diagnosis considered confirmed.

Can it be prevented?

Keeping an active healthy lifestyle and attitude, smoking cessation and eating sensibly are important in most patients with symptoms of chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dietary therapy for reflux is mainly based on avoiding obesity, minimising fatty or spicy foods, chocolate, mints, irritating soft drinks and reducing alcohol and caffeine consumption. Other helpful measure include: increasing fruit and vegetables and dietary fibre, 30 degree head elevation during night-time sleep and losing at least 5% weight. It is best to first change the behaviours that contribute to heartburn. If the pain persists, medications called PPIs taken half and hour before a meal are highly effective.

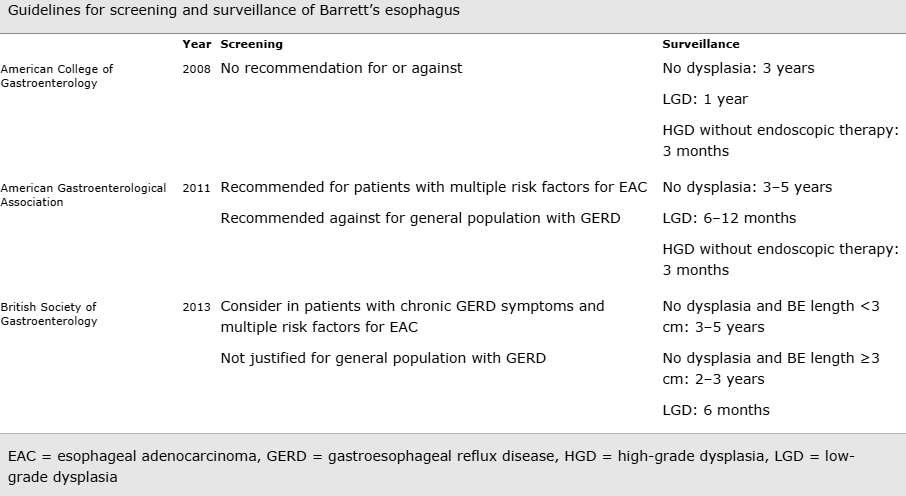

To date 2014, there is no convincing evidence that gastroscopy screening in reflux patients for Barrett’s eosophagus prevents cancer. Equally, when Barrett’s is found, it is questionable whether controlling heartburn symptoms with medication (so called chemoprevention) or surgery, or taking aspirin will lower the already small risk of oesophagus cancer. So, if there are no reflux symptoms, medications are not essential. No society guidelines currently recommend PPIs or NSAIDs to prevent oesophageal cancer in Barrett’s patients.

What is surveillance?

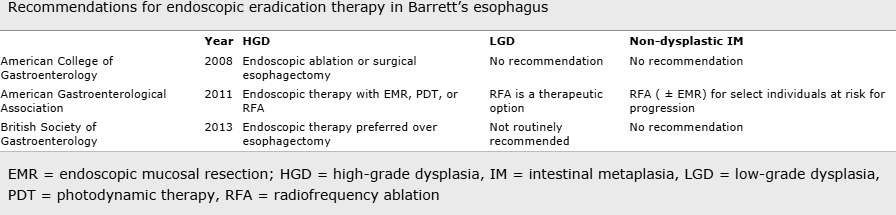

Much like having a pap smear to prevent cervical cancer or a mammogram to prevent breast cancer, regular gastroscopies are recommended if you have Barrett’s oesophagus. This allows your doctor to pick up dysplasia – early “high risk cells” – before cancer develops. If an early cancer change is detected on biopsy, surgery is generally recommended. However, newer ablation techniques may be offered. A common approach is to biopsy thoroughly newly diagnosed Barrett’s to look for dysplasia after 6 weeks of a daily acid lowering pill. Taking this pill before biopsies, increases the chances of a clear diagnosis. If no dysplasia is found this is good news and, depending on your situation, expert opinion includes either to have no further surveillance or, to have a gastroscopy every 2 -5 years.

Is it best eradicated with surgery or endoscopic ablation?

A tailored approach

For example: if I were a 50 year old caucasian, obese (BMI>30) male who smoked with longstanding reflux symptoms, I would seek a gastroscopy to screen for Barrett's oesophagus. If my specialist found 9cm [ie. 'long segment' (>3cm)] non-dysplastic Barrett’s then I would want my pathology slides reviewed and the diagnosis confirmed by a second expert GI pathologist. I would then want to be put in a Barrett's surveillance program and have gastroscopy every 3-5 years. The benefit of PPIs or aspirin to prevent oesophageal adenocarcinoma is questionable and I would only take PPIs for symptom control.

Endoscopic screening and surveillance is not without costs and risks. Studies have shown that a diagnosis of Barrett's oesophagus causes psychological stress, has a negative effect on quality of life, and results in higher premiums for health and life insurance. If I were female without without a family history of oesophageal cancer and on gastroscopy my specialist suspected the commoner short segment Barrett’s (only <3cm) then I would not want to know nor have biopsies taken to confirm this diagnosis. This reflects a comfort level with uncertainty and very low risk of oesophageal cancer. Statistically, in this second scenario, I am likely to be a “safe Barrett’s” where the diagnosis brings unnecessary anxiety and gastroscopies every two to five years for little gain.”

Clearly different people deal with life’s risks in different ways. In the future, we hope to be able to pick with certainty “safe Barrett’s” from “high risk Barrett’s” patients, reassure them and send them away. While we await that time, how doctors manage Barrett’s is very individual. Despite all, most doctors recommend and most patients still choose regular surveillance gastroscopies even with the low risk short segment Barrett’s.

Spechler SJ, Souza RF. N Engl J Med 2014;371:836-845